The Wool Cocoon

Re-wilding our Final Transformation

A conversation with Yuli Sømme

If each of our bodies were looked at under a microscope, less than half of what we would see would be human cells. Our bodies, are not just ours and we, are not our bodies. If we didn’t have this thriving microbiome both inside, and outside of ourselves then bluntly, we would die. There’s some food for thought, or, for soil.

It seems unjust then, that we humans feel ownership over these cells. What if that when we die our bodies aren’t locked away from the earth within the rigid walls of a coffin, but given passage of transformation, enshrouded in wool.

Wool is completely biodegradable, even in water, and has been lending us it’s super fibre benefits for thousands of years. We have knitted it into jumpers, woven it into blankets and rugs, used it to line the walls of our homes. In 1666, England introduced the Burying in Wool Act as an attempt to revive it’s depleting native textile industry, it became a finable offence to be buried in anything else and although this technically remained until 1873, it was tricky to enforce.

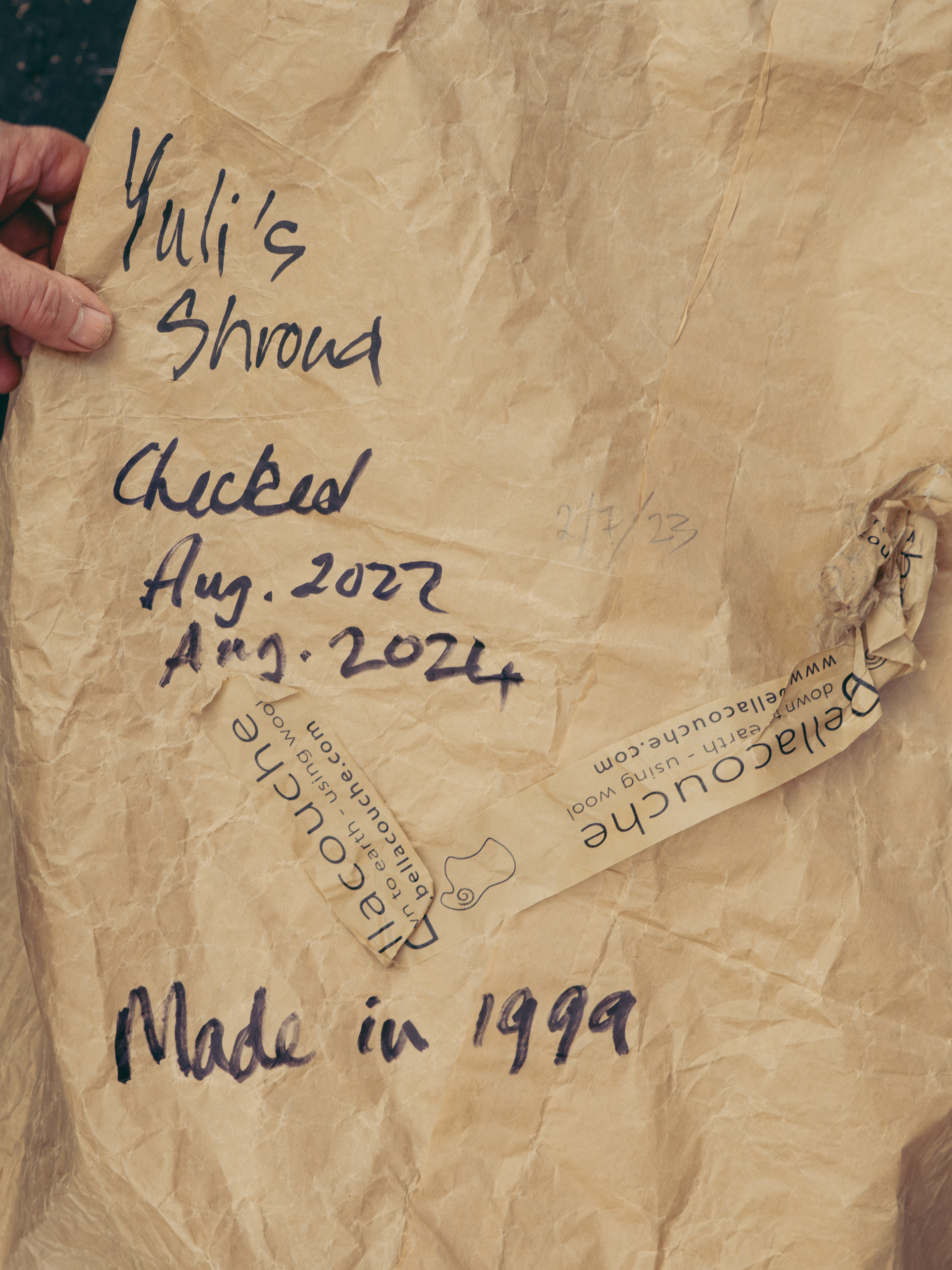

Yuli Sømme co-founded Bellacouche over 20 years ago after learning about the 1666 act, feeling its necessity within a modern context. She remains one of the few shroud makers in the country and on the eve of passing the business into new hands, I paid her a visit.

‘And she took her children to the low lands’, reads a felted wall hanging in the workshop of Yuli Sømme. Yuli was only five when her mother moved her and her siblings from Norway to Devon, England following her father's death. She recalls looking to wool as a comfort, being dressed in Norwegian votter, mittens with delicate patterns, and learning to knit from her mother.

YULI

Although she was english, she was a great knitter.

There wasn’t grief counselling for children at that time, there wasn’t much grief counselling at all for anybody, but particularly for children. It was kind of like a non-thing recognised as a need for children. I didn’t even go to his funeral, I didn’t know what it was all about, I didn’t understand anything. I found wearing his garments or my mother’s woolly jackets very comforting. So that’s how I really got the feeling that wool was my thing without thinking about it.

Decades later, I wanted to create an art piece for an exhibition called Treading Lightly. I’d been to a museum in York where they had a whole thing about burial in wool from the 1666 act and It inspired me to think about the whole cycle of life and how we human beings have disrupted it. It’s why we’re in the pickle we’re in now. We have disconnected ourselves from nature. I wanted to do something about it, around that whole life cycle, so I created a tableau based on birth, marriage and death. My exhibition pieces were a woollen baby’s nappy and a woollen changing mat - when I had my children, they had woolly nappies with muslin inside, so I’d sort of already experienced that! - Then I made two wedding capes for the couple getting married and a shroud for death, handmaking the felt. The wet felting process is very arduous, long, and tedious and takes days and days of rolling the felt. Somehow though, that was very cathartic for me as somebody who was a bit traumatised around the subject of death.

After that exhibition, I was rung up by a local woman who said ‘my husband’s dying, can you come and measure him up for a shroud? Oh, and by the way, can you make it out of his wool?’ (he kept sheep) I thought, okay, well, yeah, I’ll follow this track, you know, see what happens.

And that’s really how it all started.

I started working with a friend, Anne Belgrave, a felt-maker, and she and I were feeling that we were really connecting well with the whole idea of it. For a few years, we just travelled to each other’s places (she’s in Wales and I’m down here in Devon) to work together on what is it we’re trying to create because nobody else has. There aren’t any shroud makers around, or there weren’t at that time. We wanted to create something that was fit for modern funerals, but with, you know, an ecological thread to it.

The shrouds I made right at the beginning whilst I was experimenting, I found that they really changed me, they really changed my whole attitude to death. It was very helpful and it became ritualistic, quite cathartic and releasing, it really helped me so much because the subject of death had been so difficult for me throughout my childhood.

ZOË

Do you feel like you see death now as a natural and warm thing rather than something to be feared?

YULI

Absolutely, absolutely. I’ve had the privilege, especially in the last few years actually, in being asked to effectively be a funeral director. It’s not very often, and I haven’t set myself up to be that, but when I have been asked, it’s been a beautiful thing

It feels like rescuing a body from a mortuary, and I know that the family, or the people around that person, have felt that too, that it was a great relief to bring a person who they’ve loved home from a very clinical place. Mortuaries are just so impersonal and to take them away from that and bring them home to a home setting is an amazing thing. Wool is very insulating, I can put them straight into a shroud on their bed, or on a couch, and just using ice packs, I can keep them chilled for ten days, twelve, a fortnight. When you’re tending a body every day, you’re making sure that nothing’s wet, that the ice isn’t creating damp or anything, so you really go deep into what this is.

Again, it becomes quite ritualistic, and I’ve been helping other people take the process on. I’ll start it off and then they’ll take over. It’s a way of taking control of what’s happening because, we’ve been persuaded as a species that it’s all best done by the professionals.

As somebody dies, they are put into big plastic things, zipped up, and taken away.

Then you don’t have to think about it or face it, now that might be what some people want, and that’s absolutely fine, it’s convenient. But the way that I’ve been doing it has been an alternative. It’s going back to the old way, and I think that on an emotional, soulful, and an environmental level, that it’s something that is very invaluable. You can’t put a price on it.

ZOË

Your shroud is called a leaf-cocoon and that really interested me. How does the word make you feel? Why did you choose it?

YULI

Well, maybe I should show you my first one, I’ve still got it here. Well, one of my first ones, and It’s going to be the one that I will be buried in. It is a cocoon shape and there’s a leaf over it.

I like the word. Coc-oon, it’s a beautiful word, isn’t it? Yeah. And there are probably hidden cocoons in here of moths I don’t want…so it’s a nod to them!

ZOË

Yeah…yeah, it is a nice word. And it kind of reminds you of how they prepare beings for another for another life.

YULI

It does yes, it’s part of that isn’t it. Actually, I hadn’t thought of it quite like that, but that’s lovely.

ZOË

A butterfly was in a cocoon.

YULI

Yes, and then the butterfly emerges. So, in the ground when you are buried, you kind of emerge as something else. Soil, basically, and then that gives way to new life.

That’s a lovely way of putting it actually.